The Eye of the Acoustic Storm

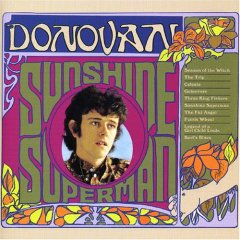

Donovan

Each week, a different artist is spotlighted in “The Eye of The Acoustic Storm.” Hourly segments of “The Eye” feature the artist’s music along with bio information and sound bites.

Born Donovan Leitch in Glasgow, Scotland, he made his initial impact on the British music television show, “Ready Steady Go.” Soon after, he was known simply as Donovan, and scored major hits with “Sunshine Superman,” “Mellow Yellow,” and “Atlantis,” among others. Donovan made it into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2012.

The Acoustic Storm Interview

The Acoustic Storm spoke with Donovan on February 7, 2008 at the Wyndham Hotel in downtown Phoenix. He had performed in concert the previous night at the Orpheum Theatre in Phoenix.

ACOUSTIC STORM: Your autobiography, “Donovan: The Hurdy Gurdy Man,” which was released in December of 2005, chronicles not only your life, but 40 years of music in the making. How would you describe the experience of putting together your memoirs? Did you keep a journal when you were younger?

DONOVAN: When I decided to seriously sit and write some memoirs, I was very pleased to find in an old shoebox feverishly handwritten notes that I’d made in reams and reams of paper in 1970 where it was clear that what I was capturing was the life before 1965 in bohemia and that would have to be a very important part of my book, because it was much more interesting than what was going on before 1965 – almost. Because this was the great melting pot, the great bohemian life that I’d, at the age of twelve, realized that I needed to be part of, just like Rimbaud in France, heading for Paris. I would obviously be heading for London. But I was in the world in my mind anyway through books. Through Kerouac, then on to Alan Watts, then Ginsberg, and then T.S. Eliot. My father had read me poetry from a very early age, so I was very well-schooled in poetry, but it was a great explosion of awareness that came over me when I entered campus at 16 years old and became aware of bohemia. I knew that’s where I belonged.

So that bunch of papers that I found probably in ’86, was a great find because it was characters, feelings, travels with Gypsy Dave into some dives, I would say, this was the Puerto Vallarta of Britain. You know, Puerto Vallarta in Mexico was a destination for 1950’s bohemians in America and Key West and other sort of, tropical areas. This was our Riviera in Britain – St. Ives, Cornwall. And it was a 100 year-old artist community, you know. So, these notes were full of the life before 1965. And of course there were the diaries, which were very clear. But really, the true answer to the question, how did I go about it, it was staring at me, all the time. My songs are my life. And, songs tell the stories. So all it would have to be if I needed to conjure up a time, a feeling, or memories, I’d just put on the record from that particular year. Or the records of others, like Miles Davis “Seven Steps to Heaven,” or the poetry read by William Butler Yeats, or the “Bowls of Bengal,” that extraordinary record, or the Gregorian chants, or the music of Jules Beam. So I could stir up these memories very easily and start writing. But of course, that wasn’t going to be the easy way out, I had to learn to write and so I wrote too much.

And I wrote everything, all the way up to 1990, and it became like “War and Peace.” And when I showed it to Chronicle Books in San Francisco, they said give me a picture book, I don’t want “War and Peace.” And I said, you’re right, it’s just too long. So in actual fact, my memoirs only go to ’70. Because when I finally had it in such an order – I had it in an order I liked, then I learned how to write. Marianne Faithful and she’d already released her book, so I said I’m writing my book and she said, Oh Don, when you get to the publishing stage, you’ll be introduced to the blue pencil. And I said, what’s that? She said, oh, you’ll find out. ‘Course the blue pencil is editing and the editors just go through huge areas of the book saying, out, out, out, and so the things that you thought were most precious about have to go in the interest of the narrative. So I learned a bit of that as well. But then I got a call from Random House in London, Mark Booth said, I’ve heard you’re writing a book. And I said, well, yeah. And he said, well can we have it? I’m a junior editor at Random House. I said, well, it’s not ready. Ten years later, got the call from Mark Booth again, who said, I hear that you’re on to the book again, do you remember me, ten years ago? I said yeah, Mark, how you doin’? He said, well I’m the senior editor of Random House, now, are you ready? I said, Mark, I think I am. And so we sat down and we decided to go to 1970. But with lots of stuff before ’65.

AS: Growing up, what were some of your early musical influences and inspirations, and then how did you evolve as an artist?

DONOVAN: Well when I first heard music, this time ‘round, when I say this time ‘round, I feel I come from a tradition in the Celtic and pre-Celtic Irish and Scottish tradition which means that the music can travel through time. And a young child can seem to have a talent at the age of three and be encouraged in Scotland and Ireland, because they know something is being carried on. And so, without going into too much detail in reincarnation, I felt I was part of a tradition very young, even before I was 14. And I heard the tradition all around me in Scotland. The first music I heard was folk music, and popular song that my mother and father would listen to. My father would listen to Billie Holiday and jazz, but also Scottish music. My mother would listen to Frank Sinatra, I guess, and musicals. But at home, a chair would be put in Glasgow in the front room, in the center of the room at a party and each member of both sides of the family would be encouraged to get up and sing a song. And so I was aware of the Scottish songs and also the sad, leaving songs of the Irish, ‘cause I’ve got Irish and Scottish, mostly Irish. We lived in Glasgow, born in Glasgow, which had a great Irish community, just as Liverpool has a great Irish community, which also produced extraordinary music – Lennon, McCartney, Irish names of the Beatles, and so on. But I listened to that kind of music, which was naturally sung by relatives, without an instrument – no piano, no guitar, just a cappella. And then I moved down to England when I was 10 with the family, and spent my teen years within 20 miles of London, and became aware of the radio, of course.

When I was listening to radio in Scotland, it was usually radio plays. Popular music of our generations wasn’t really played until ’55 on the radio, something like that. But my father took me to see “Rock Around the Clock,” for some crazy reason when I was 10 and the Teddy Boys were tearing up the seats to this movie of rockabilly. And that must’ve entered me, because I remember it so well. And then at 14, as a teenager, of course I was listening to the Everly Brothers and Buddy Holly, not knowing that they were folk musicians essentially in their tradition. Not knowing that Phil and Don Everly, who I’d meet later, had an Irish granny, who sang them songs of tradition. I didn’t know any of this. Not knowing that Presley was a Scottish-Irish name and the tradition of singing was coming through Elvis. Not knowing any of this, I fell in love, of course, at 14, with schoolgirls and pop music. And it was the Everly’s and Buddy Holly. But then that jazz was in there. That Billie Holiday at home was in there. That poetry my father had read me. Very well-schooled in the ballad form, but he never sang. He read me the meters of ballad – da daah da daah da da da, da dee da da da, da dee da da daah da da da da, da daah da daah da daah. This was the story-telling ballad form of the ages, you know, and it had been part of folk music forever. I didn’t know that.

When I entered the campus at 16, I was fully plugged in because now the teachers were potters and painters, now the fellow students were sons and daughters of radical families. Now those sons and daughters were studying painting and poetry. There was a common room where jazz was played, and then of course, I became fully integrated into the life that I knew I was part of. I saw it in the life of Paris in the ‘50s in photographs, and when I read about Montmartre and Paris and how it had been an oasis from 1890, an oasis of cultural bohemia, I felt I was part of it. Then I listened to Woody Guthrie, and that was it. Not only the Jack Kerouac books leading to Buddhism and spiritual path and poetry, but this extraordinary man, Woody Guthrie. He mirrored my father’s union-socialist background, he wrote his own songs constantly, he was for the working class, not exactly from the working class, but he bummed around and traveled. And before I even heard of Dylan, I was well into Woody Guthrie. And Guthrie’s another Irish-Scottish name. So the tradition continued through folk music. Joan Baez is half-Scottish and half-Mexican. She recorded nothing but Irish and Scottish songs when she made her first records. So it was all coming together in a very beautiful, interlaced pattern which I would become aware of. That American and British and Irish and Welsh and Scottish music was woven together and had created pop music. That was the great excitement, that it was all from the same root.

AS: How would you describe the appeal of acoustic guitar and other acoustic instruments?

DONOVAN: Well it’s very old, the stringed instrument. There is a debate and there was a novel from one of those great South American novelists, I can’t remember his name, who explored the origins of music, the human music. Was it flute, by taking a little piece of wood and making some holes in it, and letting the wind play through? Or did they hear the wind playing through the trees and want to mimic the birds? Or was it the drums? Where would the human have heard the drums? All these are mysteries. Then of course, there’s the stringed instrument which seemed to have come out of tortoise shells, or for instance the ancient paintings, vast paintings of Greece, you’d see the stringed instrument, the kythera, and there were two different sizes to the lyre. You know, the big one and a little one. And then you think of Africa, and nobody thinks of Africa. Everybody forgets Africa. You know, they say the cradle of mankind, you know. But the stringed instrument is very interesting. How did it appear? There were no metal strings. Extruding metal strings – it was gut. The original nylon classical guitar was strung with gut. And so, all this is very fascinating and worth a whole program on itself.

But for me, the guitar is a very personal instrument. You can carry it, as the harpists did – some of the big harps were carried by a road manager. In ancient Ireland, just recent ancient Ireland, there is a book about Carolan, who is the last documented harp player of Ireland. He was blind, just as the stories of Homer and other great bards of the past are supposedly blind, so he had a road manger who carried his harp. And they had two horses and they traveled from castle to castle, from great seat to great seat, festival to festival, once again a stringed instrument. For me it’s very personal. I love the idea you can hold the instrument and can call your guitar a girl’s name, a female name perhaps. It’s because it’s pear shaped, the guitar that has come down to us. It sits comfortably in the lap, six strings is a very interesting combination ‘cause there presumably were seven strings on ancient harps and they were related to the planets, according to Plato and Aristotle. The sounds, the keys and the notes and the chords are all combinations of notes that emit from seven planets in the solar system. And these are related to the seven chakras. And so as I got into it deeper, I started seeing and hearing explanations of it, but I had already learned as a young man in this life the effect of the acoustic, wooden guitar on an audience. It’s very powerful.

AS: How did you develop your unique vibrato vocal style?

DONOVAN: My vibrato came naturally. It may have been listening to the great Billie Holiday. Her own vibrato she learned from saxophone players. The vibrato of my own records came quite naturally but it’s very slow. Neil Young has one, which is even slower. If you ask them all, I think you’ll find it was natural. But it may all be related to the saxophone. It’s like a human voice, the saxophone.

AS: Let’s talk about some of your best-known songs, starting with one of your earliest, “Catch the Wind.”

DONOVAN: A poem, to a love that I hadn’t met – Linda. Performed in the third week of my television presentation of my work on a show called “Ready, Steady, Go.” Became #3 and was my introduction to the world of recording.

AS: What was the inspiration behind “Sunshine Superman?”

DONOVAN: Another song for my Linda, my muse. Written in late ’65, showing that we would meet again. She and I couldn’t continue together in that late ’65, as my book describes. That’s the commercial for the book. “Sunshine Superman,” a breakthrough sound for me – the masterwork would become an album called “Sunshine Superman” where I would explore in late ’65 and early ’66 a fusion that would open the doors for every musician in the world to experiment likewise.

AS: There are also some references to a comic book hero.

DONOVAN: A great love of comic book art, we all came through art school in some way or another, we songwriters of Britain, and of course film-makers, and novelists, and poets, and dancers, and choreographers, and designers, and hair dressers – the British art school was pretty much “it” in all the cities of Britain which became the breeding ground of British bohemia over the decades. And so one of the discoveries was pop art. And so when I realized that I also loved comic books, a comic book hero entered “Sunshine Superman.” It wasn’t just the Superman of DC Comics, but it was the super man of Nietzsche, the super man of yoga, who would now become the full potential of the human being. So there were many items in that song, not only a love song.

AS: How about “Mellow Yellow?”

DONOVAN: “Mellow Yellow” was a jazz groove that I learned, the feel of the groove, in Preservation Hall in New Orleans one month, early in my career, it must have been early ’66. And I came back to London and I just used to sing this thing in parties, and my producer Mickey Most said, ahh that’s it, that’s the next single. I said, what, this? He said, yeah. And so it was. And to be mellow and to feel mellow was the cool groove of “Mellow Yellow.” And the greatest accolade I got was from Dr. John, who said, yeah man!

AS: I’m wondering if you may have written “There is a Mountain” when you were in Jamaica? Of course, that melody would go on to become the basis of the Allman Brothers’ “Mountain Jam.”

DONOVAN: Well, “There Is a Mountain” is very influenced by the Caribbean, I mean we grew up, we British musicians with the black Caribbean community all around us, especially in London and Birmingham, Manchester. And so, just over the tracks was blue beat, reggae, which would come later, calypso – Caribbean beautiful rhythms, so it was all around us. But I did, when I went to the islands, start picking up what they called this island scratch, scratch beat. Which is what “There is a Mountain” is. So it was a scratch beat. And, like I was saying, George Harrison, John Lennon, and I were forever introducing teachings into seemingly harmless pop music. There would be teachings inserted, that you could sing along and jive along, but if you said, I wonder what the lyric means, and then you’d look into it, which today you can. It’s a haiku poem. It’s also a koan, a zen koan to put your mind in a certain space, to consider a certain truth. To break certain conditioning, it’s a zen koan. First there is a mountain, then there is no mountain, then there is. And the lock upon my garden gates – the snail, it all points towards being fearless in your life. And these are seemingly harmless, simple phrases, but they’re very deep once you’re studying meditation. So, it was a combination of all that, then a lot of fun, as well. “There is a Mountain” was a favorite of Little Stevie Wonder, when he was little, Stevie Wonder. When I met him in 1967, he loved that song, yeah.

AS: What do you listen to these days?

DONOVAN: Well, you know, when you hear a new artist coming out and she or he’s with a band it’s possible they were actually from the folk world and the producer and them got together. How do you pronounce her name – Feist, I mean she begins in a singer-songwriter’s mode and then it made me think, wait a minute, it’s all singer-songwriter, and it’s all acoustic, everything. The Beatles, when you first see them – they’re not only playing electric guitars, they’re emulating the Everly Brothers and they’ve got two acoustic guitars with pick-ups, you know those Gibsons, those black Gibsons that the Everlys’ played. And then they realized the songs are not written with the band, they’re written with acoustic instruments, piano or acoustic guitar. So when you get a rock n’ roll band doing an unplugged, for instance, you say wow. Well, basically it’s all unplugged before they plug in, because you can’t just sit around with the guitar amps blasting in the middle of the night in a hotel room. But in the middle of the night in a hotel room is probably where the best songs come — or sitting on the beach somewhere with an acoustic guitar — or in the back of the bus on the way to the next gig.

So acoustic guitar, more than piano, is really where all the songs begin. So a new folk artist, like Beck when he came out, not Jeff Beck but Beck – when I saw Beck first he was acoustic. That’s what I told my son, Dono, Jr., living in L.A. And he said yeah, he can’t afford a band. I loved acoustic, and wanted to be acoustic. I didn’t want a band, but it must be also an economic choice, you know. And also, you learn, you cut your eye-teeth, you learn your craft when you’ve got one instrument and one voice. Very, very quickly you learn it. You learn whether your guitar playing is enough to support your work, to sing. And then you learn a lot of tricks, you know, of how to perform. Which songs to put first and which to save, and stuff like that. So everybody’s acoustic. It was very clear that Jewel, when she arrived, was an exact example of someone who couldn’t afford a band, but performed with acoustic guitar totally, completely out of the tradition, without her even knowing it. She just stood up and played – sang and played. And that’s when Neil Young commented when she performed, I think, in front of him to a huge audience and she was kind of nervous, and he said to her – I read this in Rolling Stone – Jewel, remember when you stood up on the table in those bars in Alaska? Just go out there and sing, feel that you’re playing to a bunch of people that don’t really usually listen and force them to listen. And of course, she did. And so, she then worked with bands, of course. And then you have the acoustic, vocal new artists becoming very successful with a band sound.

But when we were in India, the Beatles and I, we only had acoustic guitars. And it completely colored their “White Album” that followed. It colored it in that acoustic style. ‘Cause all I was doing was sitting around playing acoustic. So they were very interested in what I was doing. And John especially wanted to know the claw hammer, the guitar picking. And when he learned it, he wrote in a completely different way. So in a way, I was the door to lead John and Paul, and George to a certain extent, back to the root of the acoustics. And they brought their acoustic guitars and George brought in sitars and tambouras and some tablas for Ringo. And so you might say that we were playing folk music. But really we were playing roots, back to the roots. Sometimes I hear in the new artists that come along, my own styles. I’m very proud of that, to have opened doors for new artists.

AS: As long as you mentioned the India trip, was this when you were first introduced to Maharishi Mahesh Yogi or had you started to practice meditation before then?

DONOVAN: I say in my book that I had actually heard of yoga and meditation before, during my bohemian beginnings, and George Harrison and I had spoke and read, and exchanged books. He gave me an autobiography of Yogananda and I would give him the “Dharma Pada” and the “Diamond Sutra,” and we’d speak about learning meditation. And so it’s a great pleasure to speak of the journey to India which I made in February of 1968 with John, Paul, George and Ringo, one Beach Boy, Mike Love, Paul Horn, the jazz flutist and our friends.

Because this year, 2008, is the 40th anniversary. And for two years now, Linda, my muse wife, and I have been developing something to celebrate. What could we celebrate, obviously a concert. Linda and I have been working closely with David Lynch, the master film maker, who has created a foundation, the David Lynch Foundation, to raise millions to give transcendental meditation to students worldwide. Which has been applied, over the years, to astounding success. So over the last two years, the 40th anniversary of the trip to India has been uppermost in my mind. And we’ve been creating a concert platform in our workshops, between Linda and I and David Lynch. In 1967, they called it the Summer of Love. In 2007, we celebrated that anniversary, and I did many interviews. It was mostly about psychedelia, sex, drugs and rock and roll, the explosion of a generation searching for an answer, celebrating life. But I was saying in my interviews last year, you ain’t seen nothin’ yet, because what really came out of the 60’s, which was the flower of the search for some understanding and an end to suffering, the flower was meditation. This was the true discovery.

A yogi came to the West and certain singer-songwriters were searching out and reaching out to the East for the technique of meditation. Maharishi brought it. My statement this week, I had to make, because Maharishi finally dropped the body, in his 90’s, this great teacher of 50 years of his mission to bring meditation back into the world, the pure, simple, effortless form of meditation known throughout the ages. There are many forms of meditation, but this one, transcendental meditation, had been proven so many times in the last 35 years to de-stress, to make the deepest alpha waves in the brain scans, this was the one lost to the ages.

This year we’re going to celebrate a concert, it’s called the Hurdy Gurdy concert, and David Lynch has stood up and honored me by saying he wishes to present it as the David Lynch Foundation presents a tribute to Donovan on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the journey to India. So, we’re looking for artists to join us, to create on stage the ashram experience, which will be mostly unplugged. Because as I was saying, when we were in India, it was unplugged. We only had acoustic guitars. The framework of the concert, raising money for the David Lynch Foundation, in America to begin, to give transcendental meditation to students worldwide – big time, I mean, big time, and we need it in these extraordinary times for students and for the world. This will be a concert where we will invite guests and the framework will be the Donovan song bag, but the songs that will be introduced at five times in the first half and five times in the second act of the performance will conjure the sounds of the jungle, the sounds of the sitar, and “Mother Nature’s Son,” which of course, Paul wrote in India. John wrote “Dear Prudence” in India after learning this technique that I taught him from the folk world. And I think we’re going to include George’s “Give Me Love.” So songs from the Beatles, mostly my own songs, but also songs that were written in India that nobody heard, that weren’t recorded, so secret songs. So this is very, very uppermost in our minds as 2008 begins, and it’s highlighted by Maharishi deciding to drop the body now. They say yogis can continue if they will, if they want. Maharishi and I wrote songs together and I will be debuting some work that we made together that nobody knows.

A further addition to this year is the extraordinary announcement I made at the end of last year in Edinburgh where I’m going to open the invincible Donovan University for Consciousness-Based Education and the Arts, where transcendental meditation will be part of the curriculum that powers the students’ highest potential, which has already proven enormous results in schools that it’s been applied to. So I have become a teacher, I am now Dr. Donovan Leitch, you may call me Dr. Don, or Don if you like. Dr. Donovan Leitch, actually it’s an honorary title, a Doctor of Letters from the University of Hertfordshire where I grew up, but didn’t attend, it wasn’t really a big school then. But I was honored in the St. Alban’s Cathedral, a thousand year-old cathedral with many of the students receiving their graduations. In the same cathedral where Brian May of the group, Queen, received his doctorate. His was a doctor of science, would you believe. He was a physicist before he became a rock n’ roll guitar player with one of the top rock n’ roll bands of the world, British of course. So, in presenting this year’s dear to my heart concert, it will be mostly acoustic but similar to your own show, a blend of acoustic with bass and drums, although the drums is an acoustic instrument and so it will be called the Hurdy Gurdy concert, to be announced where it’s going to be soon, because right now we’re inviting. And what we want to do is to invite two female, two male guests. One younger female, one younger male, and one older female and one older male. A blend of music over the last 35-40 years. We’re planning four concerts on four continents. One in America, one in the U.K., one in Germany and one in South America. But for instance in the U.K., I would love to have Kate Bush, ‘cause Kate Bush is dear to my heart but also she recorded a song called “Lord of the Reedy River,” which I wrote in the ashram. So, this is one of the songs, lesser known, in my history, but very much part of the experience in India. And so in the U.K., if one wants to try to coax Kate out of her semi-artistic retirement – she doesn’t perform live, you see, she is like Enya. When she performed live, it was for a video camera, really, or a charity. And this is a charity, this is an enormous charity event. So when you want Kate or another artist, and you want to invite them, they’re all busy themselves. So you spread the net and see who wants to be part of this great cache of musical joy. And then you figure out the ones are free and who wants to be part, and then you’ve got a window and that window could be three months wide, you know, and then you start bringing it closer and closer. So it’s really finding the artists, the guests, to create the event, and then looking for the venue. So I can’t announce it yet, but my website will, Donovan.ie, ie for island, and the DavidLynchFoundation.com.

As we’re talking of India and this is the 40th anniversary of that journey and how myself, John, Paul, George, Ringo, Mike Love, Paul Horn, brought back in a big way to the west this extraordinary, wonderful, effortless form of meditation called transcendental meditation, I just wanted to say that this week is extraordinarily historic because the guru, Maharishi Mehesh Yogi, dropped his body. I just came from Holland where he was living and the funeral will be in India. A yogi’s funeral, a ceremony of extraordinary pageant. I won’t be there, because I’m doing other things, but I just wanted to say that I’m saying to the world, when they ask me, the Maharishi brought the pure, transcendental meditation back to the world. And reunited us all with our true self. This statement is what I’m giving out, but the actual depth of that statement can be heard in my music, and in the Beatles’ music, and in many other musicians around the world who have benefited from it. It also benefits everyone. It’s a very, very historic week. And not sad – a celebration of this man’s life. 50 years, a constant mission. Influencing the worlds of the medical profession, de-stressing the world, the world of education, and as I say, definitely the world of arts.

AS: Would you talk some more about the visit to India and how you interconnected with some of the Beatles, especially George?

DONOVAN: I really connected with George in India. Why? It was really Linda, my muse and wife, pointed out, that really, George and I introduced our path songs, our absolute love of meditational inspiration. And wishing to show to our fans that sleeping inside them was all the potential they could ever possibly want and the door was through meditation and study of your own true self, just as the Vedas spoke of it. And so George and I would get on tremendous in India. And he would bring in the sitars and an instrument called tambura. Tambura is a four-string instrument that ladies usually play in the Indian ensemble. It’s really like a bass but it’s actually a drone. (Simulates the noise) That thing that is continuous in Indian music is the tambura. So I would play the tambura and George would try to play the sitar. When I say try, it’s not an easy instrument. Not only is it difficult, but you have to learn how to sit. And he took lessons from Ravi Shankar. And George and I got on really well. And he wrote some beautiful songs and I did too. We collaborated on “Hurdy Gurdy Man,” the song I wrote about the Hurdy Gurdy men. We who sing songs of love, the yogi who brought the meditation of love. The Hurdy Gurdy men down the ages are those Hurdy Gurdy men 200 years ago that would wander from town to town singing the news, passing on the news through songs. And so, George and I got on really well.

John and I, Lennon and I got on quite well too. He kind of saw this guitar picking and he said, how do you do that? I said, well, what? ‘Cause sometimes I just play and I don’t know what I’m doing, it’s become second nature. He said, that. Ah, the guitar pattern. It’s moving so fast that it’s hard to know what’s going on. In fact, last night, at a concert in Phoenix in the Orpheum, someone said, I’m a guitar player, tell me – there’s two guitars on Universal Soldier, that record you made. I said, no there’s one. He said, oh. Meaning, oh, I’ll never get it, ‘cause I thought there was two. And then he mentioned two or three other songs and he said, two guitars on there, right? I said, no just one. I said when I became aware of what I was doing, it was second nature. But I was doing things that sounded like two guitars and that’s what John said, how do you do it? I said it’s a secret and it takes two to three days to show you, it’s a pattern. And he said, I’ve got days, Don, show me. So I did. And I hope to share this with the world soon, not only that style but other styles that I discovered for myself. And the next book will probably be the Songwriters’ Guide to the Galaxy or a similar title. Don’t rule out show style, ‘cause style, guitar style invents song, I realized. So I sat down with John in the jungle in India and he learned the claw hammer. And songs came – “Dear Prudence,” “Julia,” “Crippled Inside.” A new style of song writing came.

And I was very proud to have passed that on to John. And somebody said recently, you just pass it to John. I said what do you mean? He said, you passed it to us, ‘cause we learned it from John. Because John was just learning it and it was very simple what he was doing, we could learn it. ‘Cause when we listen to your records, Donovan, you’re moving too fast and too sophisticated for us to even learn anything from your records. And it’s true, my – the style moves really fast, you know and the nuances are so swift that it’s hard to learn it, what I’m doing. Paul McCartney, he refused. He said, no I don’t need to learn that. But he was looking over my shoulder and John’s shoulder all the time. As he was walking by he was listening and looking and, and then he kind of learned the style in his own way. Which is the way he had to learn it. It was better that he learned it that way, ‘cause he invented another style and you can hear it on “Blackbird” and “Mother Nature’s Son,” and many other styles. It allows you to play bass and chords and melody at the same time. Therefore, just playing without thinking, when you just get up in the morning, and you’re not thinking and you’re just playing, melodies appear from nowhere. It’s stirring the cauldron of creativity to learn this style. And it’s called the Carter Family Style, the claw hammer. Why? ‘Cause the old lady, the matriarch of the Carter Family in 1920’s, the first royal family of, I suppose popular American folk music, transposed banjo style of picking to guitar. Just as Segovia, the great classical Spanish guitar player, transposed Bach to the guitar. Segovia saved the guitar for the 20th century and the future by popularizing it. But the only way he could do it was to make it serious, so he transposed Bach to guitar and then the whole world saw how beautiful this instrument was. Before it had been flamenco, and folk, and a nice thing to see in a painting with a woman with a very large dress and a big haircut, and she has this guitar in the painting. And it was just for folk music, really. So, in a way, this kind of style saved the guitar. In another way, the Carter Family presented the guitar as a very versatile instrument, not just strumming chords.

AS: You know, “Season of the Witch” is one song that I have been trying to find an acoustic version, an unplugged version of yours, do you think you’ll ever release that as an acoustic version?

DONOVAN: I think I’ve done it acoustic – it doesn’t quite work acoustic for me, but because it’s an unplugged version it does work, and I have recorded it and it is possible to get it. I just came from New York where a lifelong dream came true, where I jammed “Season of the Witch.” It’s been a dream of mine because it’s a seminal song which has warmed up Led Zeppelin rehearsals, it’s been recorded by the Charlatans, it’s been recorded by Al Kooper and Stephen Stills. It’s been recorded by Courtney Love, although I haven’t heard her recording yet; Brian Auger and the Trinity – Julie Driscoll and Brian Auger. And hundreds and hundreds of bands have found it to be a groove jam. So I wanted to open it up, and we did in New York. Paul Schaffer of the Letterman band was on stage, Garth Hudson of the Band was on stage, along with many other extraordinary players from New York. And it will be on the bonus footage of my documentary DVD coming out this summer, called “Sunshine Superman: The Journey of Donovan,” my first documentary. Three hours long, lots of bonus footage – and one bonus is this jam of “Season of the Witch,” where we go into, would you believe, baroque “Season of the Witch,” jazz “Season of the Witch,” of course, and the Donovan style that I made on the record, “Season of the Witch.” But yeah, you can get it acoustic, keep in touch.

============

Transcribed by Sada Gilbert

Follow Us

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit, sed diam nonummy nibh euismod tincidunt ut laoreet dolore magna aliquam erat volutpat. Ut wisi enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exerci tation ullamcorper suscipit lobortis nisl ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis autem vel eum iriure dolor in hendrerit in vulputate velit esse molestie consequat, vel illum dolore eu feugiat nulla facilisis.